High levels of application engineering and technical support transform the vibratory bowl into a precise machining process.

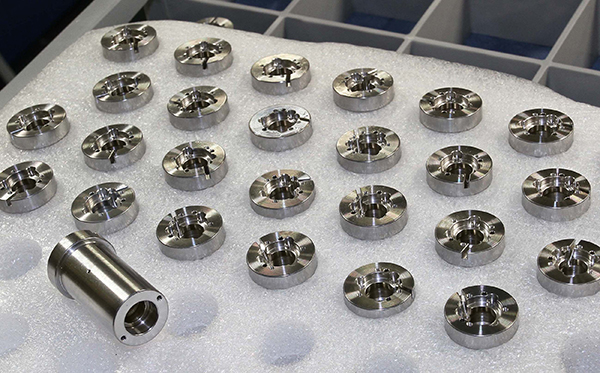

Galvanometers for laser beam steering and scanning in surgical, analytical and other applications include a precision-machined housing in which the stator moves. At the Poole factory of Westwind Air Bearings, which manufactures galvanometer components for its US parent group, Novanta, these coil housings are CNC turned from mild steel bar to within grinding tolerances.

Dimensional accuracy is down to two-tenths of a thou (5 microns), while surface roughness of the bore and outside diameter are 16 and 32 CLA (Ra 0.4 and 0.8 microns) respectively. It is curious that such precise components are then rumbled in batches of up to 400 in a pair of vibratory bowls supplied by PDJ Vibro. Many would consider the process a possible source of damage and in any case not sufficiently precise for finishing the high precision housings.

Nevertheless, by developing a viable production route that incorporates vibro finishing, Westwind has been able to save a lot of time and money. In addition, uniformity of finish is better using the automated procedure, as each component is processed consistently rather than being subjected to the inconsistencies of hand deburring.

Problems with manual finishing

Westwind started manufacturing the coil housings in-house three years ago, saving the previous cost of putting the work out to a subcontractor in the US. Four families of parts ranging from 13 to 33 mm in diameter and from 28 to 61 mm long are machined in two German-built Index C100 lathes. There are 12 part numbers, two-thirds of which are required in relatively high volumes of 3,000 per week.

John Bradley, senior manufacturing engineer said, “A lot of deburring and radiusing on the parts is carried out in-cycle by the CNC lathes. However a few whiskers often remain, which had to be removed manually using knives and scrapers, as otherwise there was a risk of fine wires being broken as the galvanometer stator is inserted.

“Additionally, fine fettling of the housing by hand with a nylon mopping wheel had to be employed to prepare it for the stator. Together with washing cycles before and after finishing, the whole exercise took three people five hours, ie 15 operator-hours, to complete a batch of 100 housings.

“Often this was not quick enough to keep up with throughput and sometimes there could be as many as 15,000 pieces queuing for finishing, with all the attendant costs associated with work-in-process.”

A further drawback was the need to take different groups of three staff away from other duties on the shop floor and deploy them onto hand finishing so that the tedious and unpopular job could be shared around.

Not only did it result in variances in deburring and mopping and hence a lack of consistency in the finished parts, but occasionally a deburring knife might slip, causing a component to be scrapped. There was also a chance of burrs being missed, resulting in returns for rework.

Advisory service

These problems no longer occur with automated vibro finishing and there have been no rejects or returns to date, despite thousands of housings having been delivered to Novanta.

It is normally team leader Martin Graham who processes the components in the PDJ Vibro vibratory bowls in a two-hour cycle, without the need to wash the parts at all. They go straight to plating after a quick air blast to remove any media resting in the bore. Overall there is a 7.5-fold saving in labour cost compared with hand processing and a 60 per cent reduction in finishing lead-time.

Understandably, Mr Bradley and quality engineer Jordan Tuxford thought at the outset, towards the end of 2016, that placing dozens of housings loose in a recirculating mass of stones would cause impingement damage. They were so concerned that they drew up plans to fixture the coil housings in jigs prior to processing in the bowls.

This is where PDJ Vibro’s consultancy service started to make a difference. Its engineers advised that component fixturing would not be necessary, provided that batches of the correct number of parts, according to their size, are finished in the 400-litre capacity bowls. Westwind sent samples to the supplier’s Bletchley technical centre and the results returned to Poole were very encouraging, as was the speed of turnaround.

Sensing that they were close to a robust finishing solution, to save time Mr Bradley and Mr Tuxford visited PDJ Vibro to carry out further trials on the full range of component sizes. It was established that from 400 of the smallest coil housings to 80 of the largest could be processed at a time without damage in the 400-litre capacity bowls.

In many finishing applications involving less accurate components and when surface roughness is not so critical, labour and time savings can result from reversing the toroidal motion of the media in the bowl and lowering a flap into the recirculating mass. Components emerge and are separated automatically from the stones, which fall back into the bowl through a screen.

However, PDJ Vibro advised in this instance that the technique should not be used, as direct impingement of component on component while on the screen could cause scratches and dents and render the housings unusable. To ensure that all parts are extracted manually from the bowls after processing, they are counted in and out.

However, PDJ Vibro advised in this instance that the technique should not be used, as direct impingement of component on component while on the screen could cause scratches and dents and render the housings unusable. To ensure that all parts are extracted manually from the bowls after processing, they are counted in and out.

Two different sizes of porcelain stone were supplied by PDJ Vibro to suit the range of component sizes and to avoid the media becoming stuck in the bores. It has since provided a third size of stone to prevent media lodging in smaller bores and achieve optimum results across all housing sizes. A further recommendation was to employ automatic dosing of water containing a mix of detergent and rust inhibitor.

Whisker removal is successfully achieved in the vibratory bowls, as well as the required high cosmetic appearance, without removing too much material and consequently altering the tight dimensional tolerances. Moreover, the two bowls are able in a single day shift to finish all of the output from the two lathes working around the clock, so there is no longer a backlog of coil housings waiting for plating.

Good customer experience

Mr Bradley commented, “PDJ Vibro took responsibility for providing a bespoke finishing package that was ideal for our application. They were very accommodating and the whole exercise amounted to a really good customer experience that is all too rare these days. We had no hesitation in buying the two EVP-400 bowls after visiting the supplier for a second time to tweak our process further.”

He added that what particularly impresses all of the production staff involved in the project at Poole is that PDJ Vibro continues to be so helpful even after completion of the sale – and not only in respect of the ongoing advice and prompt supply of consumables.

For example, the health and safety department at Westwind questioned the way in which the acoustic noise reduction cover on the bowls lowered automatically at the flick of a switch and they took the view that there was potential for a second operator in the vicinity to be injured. At its own cost, PDJ Vibro retrofitted alternative controls that require the switch to be continuously held down to close the cover.

Mr Bradley concluded, “At the start of this project, it was not clear to any of us that high accuracy housings could be placed loose in a vibratory machine and automatically mass-finished to a very high standard without damage.

“The apparent incongruity of machining parts to within microns and then tipping them loose into a vibratory bowl made us nervous, but PDJ Vibro made it work well.”